GLENN LONEY'S SHOW NOTES

By Glenn Loney, March 16, 2002

|

|

|

Caricature of Glenn Loney by Sam Norkin. |

|

[02] Globe "Cymbeline" at BAM

[03] New Audience"Cymbeline"

[04] American Drama Classics

[05] Miller's "The Crucible"

[06] Wilder's "Our Town"

[07] Adapting the Classics

[08] Ovid/Zimmerman's "Metamorphoses"

[09] Kafka's "The Castle"

[10] Met's Magnificent Music-Theatre

[11] Prokoviev's "War and Peace"

[12] "Parade" Revived at the Met

[13] Tony Kushner's "Homebody/Kabul"

[14] Eve Ensler's "Necessary Targets"

[15] Edward Albee's "The Goat"

[16] Athol Fugard's "Sorrows and Rejoicings"

[17] "Further Than the Furthest Thing" at MTC

[18] Richard Greenberg's "The Dazzle"

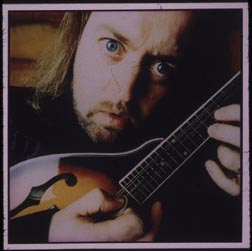

[19] "Four" at MTC

[20] Alan Alda in Peter Parnell's "QED"

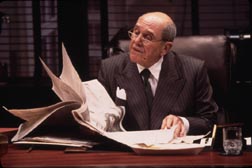

[21] Alan King in "Mr. Goldwyn"

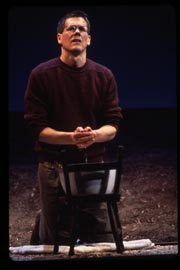

[22] Kevin Bacon in "An Almost Holy Picture"

[23] Bea Arthur "Between Friends"

[24] Bill Bailey's "Bewilderness"

[25] Daisy Prince Directs "The Last Five Years"

[26] An Aussie "Prodigal" Musical

[27] Once Again, "One Mo' Time"

[28] Mark Morris Dancers at BAM

[29] Symphonic Circus: Cirque Éloise

You can use your browser's "find" function to skip to articles on any of these topics instead of scrolling down. In Netscape, drop down the "EDIT" menu and choose "FIND."

REWORKING THE CLASSICS—

Two Cymbelines Are Not Better Than One:

|

|

|

THE WHITE ENSEMBLE--London Globe Theatre's "Cymbeline." Photo:

©John Tramper/2002. |

|

Pericles was also mounted in Manhattan. And way out West, at both the Ashland and the San Diego Old Globe Shakespeare Festivals.

Henry Hewes—at that time theatre critic for the Saturday Review and editor of Best Plays—joined me on the Balboa Park greensward to watch the Elizabethan Dancing.

Henry shook his head, but not about the ferocious joy of the dancers. "Glenn, do you realize we've seen four productions of Pericles this season? In the 19th century, the play was never performed! Critics experienced it only in print!"

Ian Richardson had shown me—just a few weeks before at Stratford—how difficult it was to speak Pericles' lines, as they are not all by the same hand. Some are obviously not from Shakespeare's pen.

Yet, Pericles is a better, more interesting play than the patchwork that is Cymbeline. The New York Shakespeare Festival revival at the Delacorte Theatre in Central Park should have demonstrated that resoundingly.

Nonetheless, that did not discourage Theatre for a New Audience—at the Lucille Lortel—and Shakespeare's Globe Theatre—at BAM—from pawing over this cut & paste playscript yet again. As the soldiers cry out in Hamlet: "Look where it comes again!"

At least our more avant-garde theatre geniuses have refrained from mounting two or three productions of Timon of Athens this season!

Shakespeare's Globe Theatre Cymbeline [**]

Mike Alfreds' conceit of having a small consort of six players—in loose-fitting white blouses and trousers—impersonate all the characters in Cymbeline made extreme demands on their varied abilities to shift in an instant from one role to another.Mark Rylance—artistic director of the Globe, on London's South Bank—achieved the effect most successfully. What's more, by playing the two men most interested in the love of the heroine, Imogen, he had a ready-made strong character contrast.

His version of Cloten—the evil queen's cloddish son—was richly amusing. His slow wits were obviously defeating his mock-heroic efforts to make a princely impression on those around him.

The small raised open-air stage of the London Globe is the product of countless scholarly arguments and seminars—in some of which your reporter participated. It is clearly better suited to this compact, intimate staging than the broad expanse of BAM's Harvey Theatre in Brooklyn.

Even using the Peter Brook Carpet-Play device to make this strange moral tale of Romans vs. Britons more intimate, interesting, and accessible did not work well. The problem was compounded by the unfortunate fact that several of the players were not up to the demands of the play and the concept.

Some audience-members left before the play was over, alas. Now they may never find out how it ended…

Shakespeare's New Audience Cymbeline [****]

Unless, of course, they had already seen the Theatre for a New Audience Cymbeline staging in Greenwich Village. Or the production in Central Park.Actually, in the NY Shakespeare staging, Cloten was marvelously comical in his rants and tantrums. Clearly, the best performance in the entire production. Which was more about visual style—stunning, in fact!—than about ensemble or virtuoso acting.

Those who have read the play—on class-assignment, or in hopes of enlightenment or enjoyment—are most often puzzled at the complications of the plot and the leaden quality of much of the writing.

This is Shakespeare near the end of his writing career? And this is what he has to show for all those years at the Globe?

In Bartlet Sher's New Audience staging of Cymbeline at the Lortel, once again—for me, at least—Cloten was outstanding. Andrew Weems played him as a cross between a demented Samurai Warrior and an Elizabethan Roaring-Boy. Hilarious!

This effect-packed production had an even smaller stage than that of the London Globe. But designers Christopher Akerlind [sets & lighting] and Elizabeth Caitlin Ward [costumes] used it to remarkable effect. There was even a gentle Japanese-print-style snowstorm…

Some Bardolotars were outraged to discover that the two "Storyteller" narrators were dressed in snappy matching 1920s suits. And that Cymbeline's lost sons were hunting in the Welsh mountains, dressed as Wild West Cowboys.

These and other Special Effects were in fact a constant visual and conceptual delight. And the testy, majestic Cymbeline of Robert Stattel was an anchor of serious—if misguided—purpose in the otherwise manic activities on stage.

We've already had a sufficiency of Troilus & Cressida revivals, so what neglected drama of the Bardic Canon will be next?

Arden of Faversham and Two Noble Kinsmen aren't Canonic enough. And they aren't very good plays, either…

Modern American Classics Endure:

Periodically, drama scholars and theatre-aficionados question why a nation with such a distinguished tradition of playwriting and performance does not have a National Theatre.In Europe, of course, even the smallest country has a National Theatre. In fact, the smaller the nation, the fiercer the cultural pride.

In Germany, there is not one, but several National Theatres. Those in Munich and Mannheim are celebrated. But Bavaria was once an independent nation. And Mannheim was the capital of the Palatinate.

The National Theatre in Weimar boasts the spiritual patronage of Germany's greatest dramatists: Goethe and Schiller!

Those European National Theatres with the longest traditions, however, have grown out of historic playhouses and acting-ensembles which were once either established or patronized by reigning monarchs.

When kings were deposed—or beheaded—their court theatres were transformed into State Theatres. After World War I, many of these neo-classic or baroque jewel-boxes at last became public property.

Having taught for the University of Maryland in Europe from 1956-60, I came to know the excellences of many State and City Theatres. Yes, important cities wanted to show those who lived in the capitals that they could also maintain drama, dance, and opera companies of importance.

Even in the bombed-out ruins of the Second World War, Germany still had some 260 state-subsidized theatres!

From my travels all over Europe—seeing productions, inspecting shops & stage-machinery, interviewing actors, directors, designers, and Culture Ministers—I came to believe that America also deserved a National Theatre of its own.

So I wrote a book—never published, alas—called Who Needs Theatre? That title may seem in itself a good reason not to buy—or publish—such a book.

My comprehensive report on European subsidized theatre was an attempt to answer that dismissive question. Which was often asked me by friends, colleagues, and students: Theatre? Who needs it?

The manuscript was read by a number of prestigious editors—of both academic and commercial presses. All insisted they found it very interesting and even well-written. One said he sat up all night to read it.

But the final response was always in this vein: "Americans don't like to pay taxes. And they like baseball much more than live theatre-if they've ever been to a performance. And TV is free! So why should we pay more taxes to have city, state and National Theatres?"

And this: "We couldn't sell more than 5,000 copies of this title. We're looking for manuscripts which will generate sales in the range of 100,000 and up."

At one point, the O'Neill Center was prepared to publish this book, but the funding couldn't be found. How then could we expect to subsidize a lot of theatres if we couldn't even find a few dollars to help print and distribute a book about this idea?

Ten years after I'd put the manuscript up on the shelf—along with the also unpublished books The Uses of Theatre History and West African Cultural Journey—my esteemed and much better-connected colleague Bob Brustein used the title for a collection of his critiques: Who Needs Theatre?

A big question remains: if we had a National Theatre, where should it be sited? Washington? Manhattan? Chicago? San Francisco?

Or should it be always on tour, like the now defunct National Repertory Theatre?

Truth is: We now do not need a National Theatre.

There are so few new compelling plays—or our producers are so fearful of taking a chance with untried scripts—that we now can enjoy excellent revivals of Our National Theatre Heritage On and Off-Broadway every season!

Arthur Miller's The Crucible [****]

|

|

|

PURITAN ANGST--Laura Linney & Liam Neeson in "The Crucible."Photo:

©Joan Marcus/2002. |

|

With its current and admirable revival, the resonances now are said to be with the disturbing atmosphere of fear and distrust fostered by the Administration's faceless War on Terrorism. And the White House's evocation of an alleged Axis of Evil, recalling speech-writer Peggy Noonan & President Ronald Reagan's "Empire of Evil."

If viewers and reviewers wish to see Arthur Miller's powerful drama of Fear & Trembling in Calvinist New England as a Morality Play with direct reference to current events, so be it.

The larger Truth is that, in The Crucible, Miller wrote his finest drama. Death of a Salesman will remain his Signature Play, but The Crucible is a Classic Drama in the Grecian Tragic Mode.

The conflicted, lusting farmer, John Proctor, is not King Oedipus. Nor is his plain, cold, suspicious wife anything like Phaedra—or even Electra.

Yet, on the page—and especially now on the Virginia Theatre stage—unjustly threatened and attacked by the Powers That Be, they rise to the level of tragedy.

Attaining the classic Wisdom Through Suffering, both John and Elizabeth Proctor—strongly, straight-forwardly played by Liam Neeson and Laura Linney—achieve catharsis. They finally come to know themselves—and each other—even in the hour of death and parting.

For John Proctor, this electrifying moment of self-knowledge approaches Apotheosis!

Sir Richard Eyre has staged a generally competent cast. Considered as an ensemble, this is what repertory theatre used to be like.

Brian Murray is becoming more and more like Sir Peter Ustinov. Is he eligible for a Theatre Knighthood?

Thornton Wilder's Our Town [***]

A long walk along East Fourth Street—way over into the heart of Alphabet City—is generally to be avoided. Unless you have a low-rent studio-apartment there…Nonetheless, I made the trek to the Connelly Theatre recently to see a revival of Thornton Wilder's Our Town. I already knew "how it comes out," so I was reluctant to confront its simplicities and verities once again.

The news that Tom Ligon—whom I'd admired years ago in the Hippie musical, Your Own Thing—was to play the young George Gibbs intrigued me.

Also, the venerable Barbara Andres was cast as the innocent young Emily Webb: "World, I cannot hold you close enough!" Or was that Emily Dickinson?

I have long suspected that Wilder had both Emilys in mind in this drama, which was inspired by traditions of Chinese Classical Theatre.

But, instead of the bare-bones chairs and planks—against a bare-stage backwall, as in the original and innovative Broadway production—director Jack Cummings III enhanced the starkness of the script and the Ultimate Message About Life & Death with music & projections. The score drew on New England & Quaker sources.

Softly dissolving pastel projections suggested moods, emotions, and the world of nature surrounding Emily & George in Grovers' Corners, NH.

On a square platform—which also resembled an oriental stage—the players sat in specially designed chairs, simply but smartly attired in earth-colors. These were no tag-end costume-rentals. The admirable designers: John Story, R. Lee Kennedy, and Kathryn Rohe.

Cummings is obviously a young talent to watch. There was great sense of focus, power, and purpose—and of a style which did not overpower the essences of the drama.

Instead of casting a young Emily and George and having them age, the decision to reverse—with senior actors suggesting dewy innocence—worked very well. It had even more resonance, in fact.

What did not work was casting a dewy young innocent girl as Wilder's fatherly Stage-Manager. This is not entirely a Feminist Issue, for it might have worked with a more secure, mature actress…

Adapting Ancient & Modern Classics—

What is it? Have we become a Nation of Pagans? In our desperation to find famous "pre-sold" stories that can easily be adapted as plays—because we seem to lack interesting new & original dramas—our adapters tend to fall back on Greek & Roman Classics. Not to overlook the Story-Theatre Potentials of fairytales by Andersen, Perrault, and the Brothers Grimm.What's wrong with the Holy Bible? There are so many great stories from which to choose! Including THE GREATEST STORY EVERY TOLD!

With Easter approaching, this would seem a Natural. But New Yorkers are apt to find Biblical dramas only in churches these days. Often relegated to the church-basement…

There once was a time—not so long ago, in fact—when the fable of Noah and the Ark fascinated both Richard Rodgers and Stephen Schwartz.

Even Arthur Miller—in an obviously dry-spell—revisited The Creation of the World. Unfortunately, it was not an eye-witness account…

Wasn't it film-maker Dino Di Laurentiis who discovered that he could barely cover Genesis, even though he'd chosen The Bible as his operative title?

So how about some new plays and musicals based on Biblical Narratives? But not that tattered old Technicolor Dreamcoat again, please!

Mary Zimmerman & Ovid's Metamorphoses [*****]

The ingenious and visionary Mary Zimmerman has already worked wonders with adaptations of The Arabian Nights, The Odyssey, Journey To the West, and The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci.All very good books indeed. But why not now explore The Good Book?

Zimmerman's splendid adaptation of Ovid's Metamorphoses—now translated to Broadway from the Off-Broadway Second Stage—is such a visual, intellectual, and emotional delight, she should be able to transform the pieties of Jesus' Parables into something astonishing.

Framing this water-frothy production is the tale of King Midas and his cursèd gift of the Golden Touch. This lends a Signature Golden Sheen to Zimmerman's retellings of all these ancient Greek tales of human transformations.

At the Second Stage, the action was set on an end-stage, with a shallow rectangular pool before a simple door and podium. Towels were given to those in the front row.

At Circle-in-the-Square, however, lots more towels are needed. The pool is now much bigger and longer, stretching deep into the horseshoe-shaped arena-seating.

The performers also seem to have been encouraged to make much Bigger Splashes for Broadway. There are moments when Olympic Swimming Trials come to mind.

The most amusing use of the pool occurs when yellow-swim-suited young Phaeton plunges in and climbs on his yellow inflatable mattress. He could be in the pool at Palm Springs as he describes his flaming failure to control his father's Sun-Chariot on its course through the skies.

Zimmerman develops her productions in close collaboration with her actors and designers. Usually without a definitive script in hand.

I saw the wonderful Journey To the West out West at the Zellerbach Theatre at UC/Berkeley. Why didn't this brilliant visual & aural evocation of Buddhist Legends, Asian Theatre Traditions, and Chinese Designs have a run in New York?

As previously urged in this column—well before the Broadway transfer—Metamorphoses is Not To Be Missed!

The Castle—As Viewed By:

Kafka/Brod/Manhattan Ensemble Theatre [****]

|

|

|

THROUGH THE TREES--William Atherton as K, looking for "The Castle." |

|

In fact, "The Administration" or "The White House" could be metaphors for "The Castle." Or the other way around…

As Kafka's Anti-Hero K—a wonderfully baffled & frustrated William Atherton—soon discovers: You Can Never Get Up To The Castle. You have to stay down at the foot of the castle-hill, hoping for some crumbs of information or recognition.

And though you may believe yourself educated, intelligent, competent, even dedicated, at every turn you will be mocked and blocked by oafs and misfits.

On the very small stage of the MET, Anna Louizos designed an elegant rotating white cubic-frame in a snowy landscape of bare thin white trees. It provided an ice-cold, ever-changing framework for the equally chilling developments in K's increasingly deteriorating mental and physical situation.

Of necessity—as with MET's previous remarkable production of Dostoyevsky's The Idiot—this ingeniously conceived and handsomely staged adaptation had only a limited run. But it should be toured across the nation and be seen at major festivals.

It is much superior to many of the extravagantly admired avant-garde stagings seen at the Edinburgh and Salzburg Festivals.

Scott Schwartz directed with verve and distinctive stylistic flourishes.

But the MET's artistic director, David Fishelson, deserves even more praise. Both for his vision in choosing this darkly metaphoric modern classic, and also for his share—with Aaron Leichter—in this compelling adaptation for the stage.

One can only imagine what wonders Zimmerman & Fishelson might create together…

Magnificent Music-Theatre at the Metropolitan—

|

|

|

THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY--Haunting "Frau Ohne Schatten" at the

Met. |

|

If powerful dramatic rhetoric can be given vibrant life by dynamic & charismatic actors, how much more effective highly charged situations and emotions can become with musical evocation!

But, even for those who think Bellini and even Verdi are beyond them, if they are true lovers of theatre, they should not miss Prokoviev's War and Peace and Richard Strauss' Die Frau Ohne Schatten when they are next offered at the Met.

Because Frau [*****] is a strange, invented myth of Frustrated Love and Motherhood—you really do need to study the synopsis before and follow the Met-Titles™ during the performance to figure out what's happening and why—the Met's current production is an outstanding Work of Physical Theatre.

Designed and directed by the highly unorthodox Herbert Wernicke, this Strauss musical fable uses all of the most complicated of the Met's considerable stage-machinery and lighting instruments.

Opening inside the soaring confines of a mirrored cube—which wonderfully reflects the characters—the audience immediately realizes they and the production are Out of This World. Stunning! Unforgettable!

But, when it is time for the Empress who casts no shadow to descend into the Real World in search of a woman who will sell her own shadow, the glittering mirrored realms of the heavens rise upward, above the proscenium arch.

This entire stage-set has been elevated out of sight, just as an entire stage-set—representing the Dyer's factory-sized Workshop—rises into audience view from below stage-level, also on elevators.

War and Peace at the Metropolitan Opera [*****]

|

|

|

MOSCOW IN TRIUMPH--Finale of Met's "War and Peace." |

|

Among them: the famed Battle of Borodino and Napoleon's disastrous Retreat from Moscow. Never have such masses of soldiers been deployed—nor so effectively—as in this breath-taking production, staged by Andrei Konchalovsky.

As a triumph of design and production-values, this staging makes even the most impressive Broadway musical look like a theatre-trifle. With 120 chorus, 41 dancers, and 227 supers, this is one of the Met's largest productions ever!

Full credit to costume-designer Tatiana Noginova for aristocratic period elegance among the nobles, and also for utter shabbiness among the troops and peasants. There are 1,000 costumes, which require 78 dressers to help the huge cast make rapid changes for the 13 major scenes.

Praise as well to projection-designer Elaine McCarthy. Battle-scenes and the Burning of Moscow were greatly enhanced.

But the greatest triumph of this production, in a sense, came long before. With the composer's ability—with the collaboration of his wife—to envision it originally, to condense Tolstoy's epic novel into a night at the opera, and to fiercely fight to complete it, though he never saw it complete on stage.

For those who are interested only in musical set-pieces for great singers, Prokoviev's determination to tell the story of Prince Andrei, Natasha, and Pierre in edited narration has proved a disappointment.

But that makes it all the more like a musical drama, and certainly more compelling as the plot unfolds in many directions.

At the Met, under the sovereign baton of the Kirov Opera's Valery Gergiev, War and Peace had a nearly ideal cast of luminaries. In the three principal roles: Dmitri Hvorostovsky, Anna Netrebko, and Gegam Gregorian. The many other soloists were also admirable. This production uses52 soloists for some 68 individual roles!

You can imagine what this cost to produce—and how expensive it is to perform even for one evening!

Fortunately, the magnificent opera patron Alberto Vilar provided major funding. It is a co-production with St. Petersburg's historic Mariinsky Theatre, home of the Kirov and of course of Gergiev.

Vilar is a big fan of the theatre, the ensemble, and its artistic director/general music director. This has paid artistic dividends not only at the Met, but also in distant Baden-Baden!

PARADE Revived at the Met [***]

|

|

|

SO MANY BABIES--Poulenc's "Breasts of Tiresias" in Met's "Parade." |

|

Although Erik Satie's Parade ballet—with a fey book by Jean Cocteau—was not composed as companion to either Francis Poulenc's Les Mamelles de Tirésias or Maurice Ravel's L'Enfant et les Sortilèges, Dexter thought they could make an attractive triple-bill.

This was not, of course, an original idea. But David Hockney's quixotic, childlike designs for the three works attempted stylistic linkages. He suggested a subdued framework of the trenches of World War I—only 100 miles from Paris when Parade was premiered.

Along with large children's alphabet-blocks to spell out the composers' names and double as props, moved about by green-clad, cylinder-hatted Tiepolo Clowns.

Revived a score of years later, these three design-related productions now

seem themselves as dated as the originals would appear in a reconstructionist

revival. Nonetheless, talents such as Ruth Ann Swenson, Earl Patriarco, and

Ainhoa Arteta gave their comic-opera best. James Levine conducted.

Frankly, I believe it a work of genius—though different from Kushner's epic

Angels in America. There are some stylistic similarities—such

as opening with long monologues.

The Homebody of the title is a somewhat eccentric London lady—unhappy with

both husband and daughter—who dreams of far-off places such as Kabul. But

she gets her information from obsolete sources.

I was surprised—and not a little dismayed—to discover that some colleagues

dismissed the first part of the play as an extended travelogue. Were they

really listening to what was being said and speculated. And hoped for?

Originally, this was the play. And, as it now stands—as

a necessary prelude to the convoluted but revelatory plot developments in

Kabul—it is certainly not an exercise in reading from a tattered old Afghanistan

guide-book.

In the second section, her cold, distant engineer-husband and rebelliously

unfocused daughter have come to Kabul to find her—or her body, as she has

been reported as savagely torn to pieces by a Taliban gang.

In the process, they each learn a lot about themselves, confronted with

Kabul and an Islamic Wall of Silence. Or deceit and duplicity…

But the audience learns even more about the clash of cultures and beliefs

in that far-distant country where now American bombs and food-packages have

been raining down.

I was amazed at the depth and breadth of Kushner's knowledge—and understanding—of

the complexities of the peoples and customs. Not least, his sobering insights

into Muslim beliefs and traditions which are generally alien to westerners.

[As I've noted in previous columns, I used to teach in Sa'udi Arabia. Only

for six months, but long enough to learn some Arabic and something of the

effect of the Blessed Qu'ran and Shariah

Law on daily life.

[Not to overlook the resentful insights my Palestinian Arab students offered

on the creation of the State of Israel. They were former Gaza-Strip Refugee-Camp

inmates, who had been brought to Aramco by the Sa'uds.

They passionately believed that their homes and lands had been stolen by

force. And that they intended to get them back. Driving Israel into the sea

was their aim.

This was in 1957, only a decade after Israel had been recognized by President

Truman. I pointed out that the United States would never allow them to do

this, but they were not deterred in their fixations.

On 9/11, we could see how this festering hatred and resolve had matured.

I already knew something about Kabul and Afghanistanis—even before learning

more from Tony Kushner—but from newer guide-books than his Homebody.

Friends were working for the USAID in Kabul had invited me to visit: "There's

really nothing to see—maybe an hour in the suq. But

we can fly over to Kashmir & Nepal."

A week before departure, a phone-call came from Kabul: "Don't come! There's

a Russian tank on my front lawn. We have to get out of here right now!"

Kushner's playtext, as it now stands, needs editing and shortening. Whether—or

how—this will happen is a question-mark. What is not in question is that this

important drama will surely have a number of prestigious productions in the

US and in Europe.

Kushner, it's said, has been working the script over and over. But, as in

Slavs, he may well be one of those theatrical intellects

for whom reworking means adding new ideas and additional explanations to those

already in place.

Cutting is not his strong suit.

What is especially impressive, however, is his gift for aphorism, for a

potent rhetorical phrasing of what could have been a purely banal observation.

Some of these—which do not necessarily call attention to themselves by seeming

out-of-character with the person who utters them—are either poetic or philosophical.

Or both.

But Kushner is not being Neo-Shavian in this. Such expressions seem crystalizations

of his own thoughts and observations about people, places, plots, prevarications,

and pieties.

Declan Donnellan has sensitively directed an admirable ensemble, aided by

Nick Ormerod's elemental design-props. Dylan Baker, Bill Camp, Linda Edmond,

and Rita Wolf are impressive. Kelly Hutchinson, as the suicidal and terminally

irritating daughter, is annoying even beyond the demands of her role.

Serbia's so-called Ethnic Cleansing was more about religious hatred than

it was about tribal rivalries. Whatever the excuse for rape, pillage, and

general genocide, many innocent men, women, and children were horribly attacked,

tortured, and often killed.

Obviously having to trump her international success, The Vagina

Monologues, with something even more challenging, Eve Ensler

has turned to another Woman's Issue: Helping the brutalized female survivors

of the Serbian purges in Bosnia.

Shirley Knight—as a fastidious, even obsessive, Upper East Side psychiatrist—has

come to help a group of Bosnian women deal with loss, abuse, grief, and general

hopelessness.

Whether Ensler knows it or not, this is the classic PHYSICIAN, HEAL THYSELF

plot. Trying to come to terms with her difficult young assistant—who really

only wants to write a book about the women's various pains and losses—and

with the women themselves, she finds Her Own Humanity.

And Ensler encourages her neatly character-typed assortment of women to

relive their agonies. That they often do this in the verbal "Get-a-Life" style

of contemporary TV talk-shows makes the dramatic experience less than authentic.

It's more like a TV Pilot… Diane Venora could repeat her role of Zlata!

But Ensler obviously Means Well. And—even though slangy and derivative—the

dialogue is a cut above Ensler's Vagina Meditations that have proved so popular.

Even in Germany! [Is it gross to repeat: Read My Lips…]

New Plays & Old Ideas—

Tony Kushner's Homebody/Kabul [*****]

I had to pay $60 for a ticket to Tony Kushner's troubling new play about our

Current Theatre of War. Despite the fact that some local colleagues & out-of-town

critics were able to get press-tickets, this proves, I hope, how sincere my

endorsements of this drama and its recent production are! Critics seldom pay

real money to see shows they love or hate…

Eve Ensler's Necessary Targets [***]

Bosnia is at least in Europe, not way off in Asia. But—owing to centuries of

Turkish Occupation—some of its native slavic peoples long, long ago converted

to Islam. This has remained an ancient irritant to both the Roman Catholic Croats

and to the Eastern Orthodox Catholic Serbs.

Edward Albee's The Goat, Or Who Is Sylvia? [****]

|

|

|

NO GOAT ONSTAGE--Mercedes Ruehl & Bill Pullman in Albee's "The

Goat." |

|

Way back then, no one even knew what Homophobic meant.

Well, the English-language theatre has overcome that prejudice. Indeed, Gay & Lesbian themes seem to earn Equal Time with more Pope-Approved heterosexual relationships on stage.

Some of our Brightest & Best younger—they are all aging—playwrights seem almost obsessed by such topics, characters, and situations.

Now, with The Goat—which Albee has said he wrote to test theatre-audiences' limits of tolerance—the formerly taboo topic of Bestiality has been exposed in a trendy Broadway living-room.

With Mercedes Ruehl's dynamic performance as a wife who learns from a "Best Friend" that her husband is having an affair with a she-goat, this is dynamite theatre!

She is ably assisted by the bemused husband, played by Bill Pullman; their confused gay son, frenetically impersonated by Jeffrey Carlson, and by the TV talking-head best-friend, Stephen Rowe.

No, you will not get to see the goat onstage at the Golden Theatre.

Aside from the dubious values in testing Audience Toleration Through Drama, it may well be that the Broadway stage is not the most effective forum for understanding the moral, social, cultural, and economic issues involved in falling helplessly in love with your German Shepherd. Or your parakeet?

Edward Albee has managed to give a whole new meaning to Mary Had a Little Lamb!

You now may want to think twice when you refer to friends as Dog-lovers or Cat-lovers…

First of all, let it be said that this is not only deliberately provocative, but also a very professional, sleek, high-octane production. It has been tautly staged by David Esbjornson.

It is worth seeing for those values alone. You might want to engage designer John Arnone to redo your duplex!

Bestiality is a first for Albee. But not for the Manhattan theatre.

Some old-timers may remember the outrage when Tom O'Horgan staged Rochelle Owens' Futz at the Theatre De Lys, now the Lucille Lortel?

Owens' barnyard hero was in love with a pig! Really sincerely, sexually, and romantically in love!

Some senior drama critics—who wouldn't be caught dead at such a production—denounced the play and the production. Actually, it was very amusing, if you didn't take it seriously.

Tom O'Horgan—who would earn his place in Theatre History with Hair—pretended to be puzzled at the angry attacks on this allegedly "immoral and disgusting" play. As he then told me: "It is a female pig. The guy is not a homosexual!"

But this was the heyday of the Theatre of the Absurd, in which Edward Albee was then the Morning Star. But if you are looking for early signs of the playwright's interest in animal-lovers, you won't find them in Albee's —The Zoo Story.

Marion Seldes—who recently was so fine in Albee's Play About the Baby—tells me that both she and Albee are 73. This was in response to my own admission of 73.

So, can it now be, as Albee becomes the Evening Star of Broadway—after some decades in virtual eclipse—that he is revisiting the Theatre of the Absurd?

Is Edward Albee trying out some new/old seeming Absurdity? Is he searching for some strange meanings beneath the surfaces of social conventions?

At one point in the new drama, the experience of a mature man becoming erect when holding an infant on his lap is noted as an instance of strange, socially taboo, abnormal sexual behavior.

That it is both consciously unwilled and totally unwelcome, even frightening, makes a suggestive point about Albee's anti-hero's sudden, inexplicable fascination with the eyes of his now beloved goat.

That infant anecdote obviously disgusted a nearby critic-colleague. But one might also remember the odium Sigmund Freud incurred when he raised the taboo topic of Infant Sexuality…

This marginal anecdote recalled the experience of an old friend, just deceased. When his darling little daughter was still a toddler, he refused to hold her or show any physical signs of affection. He was very loving in words and gifts. But he avoided touch. I thought that very odd, for she was a great charmer.

Years later, his wife told me why. He found he was getting an erection merely by holding his baby daughter in his lap. He was horrified, as he could neither control this nor understand it. So he always kept her at arms' distance, even when she was a grown woman and a mother.

There is even a moment near the close of Albee's play when the gay son expresses physical as well as filial love for his father. This is not as peculiar or abnormal as some people might imagine. Some sons secretly lust even for abusive fathers.

So, although an affair between a grown man and a goat—which threatens to wreck a family and a career—may look like a 21st Century retreat into the Theatre of the Absurd, Albee may be serious in raising such uncomfortable issues.

Years ago, the distinguished American literary critic, Edmund Wilson, wrote a collection of stories called The Memoirs of Hecate County. It sparked an instant scandal. Public libraries banned it, and civic-minded citizens organized book-burnings.

The outrage had nothing to do with witches—or the ever-excoriated Satanism—although Hecate is indeed a Witch of Witches.

No, the offense was in a tale in which a lonely farmer had sex with his sheep. As in Futz, female sheep, of course.

Such things were not mentioned in Polite Society at that time. But among the farmers I knew—growing up on a California ranch—a standard joke was the explanation of why some farm-hands favored low-top boots: They could secure the sheep's hind-legs in them…

Athol Fugard's Sorrows and Rejoicings [**]

Some cynics used to say that the worst thing about South African Apartheid—at least for New Yorkers—was to have to see all those plays about its social evils.But this vicious governmental separation of whites from blacks—with the Native Africans always the abused victims—gave South Africa's most admired playwright the subject-matter which made him world-famous.

Unfortunately for Athol Fugard, however, the demise of Apartheid may have robbed him of his fountainhead of inspiration and passion. That these waters were poisonous made his plays even more potent and memorable.

But Apartheid is no longer the outrage—and International Cause for Concern—it once was. Fugard seems unable to focus on the serious social problems which have emerged in its wake. Or he may be uninterested?

His recent Captain's Tiger—though mildly interesting—was essentially an evocation of his youthful discovery of his writing talents on board a tramp-freighter.

Fugard's current Sorrows and Rejoicings is Post-Apartheid in time. But not in spirit.

The two women who loved a failed would-be Boer poet—one white, one black, with the silent sulking daughter of the black woman and the white man in the background—meet in the house which now belongs to the white widow. She has not lived in it for a long time, having later moved to London with her husband, from whom she became increasingly estranged.

The poet—impersonated by John Glover—appears as an often drunken wraith to comment on the women's memories of him.

But there is very little forward action or interaction. Some healing perhaps, but this is mostly a Memory Play about a man who is less than compelling, either as poet or lover.

The estimable Judith Light and Charlayne Woodard play the two women with dignity. Fugard directed, which may have taken the play's temperature down ten degrees.

Zinnie Harris' Further Than the Furthest Thing [**]

Those readers who archive old reports from the web may discover that I praised this drama when I saw it at the Traverse Theatre as part of the 2002 Edinburgh Festival. I found its tale of an small community of people isolated on the remote island of Tristan da Cunha pathetic and intriguing.Ships with supplies arrived only once or twice a year. There were no trees. And a very limited local diet. Conversation and inter-action seemed virtually non-existent.

Something terrible had happened years ago. Something no one would speak of. It had seriously affected the young man Francis, who together with his aunt and uncle, form the family triangle of the drama.

Threatened by a volcanic eruption, all the natives were evacuated and taken to Southampton in England. Newly housed and assigned factory-work, they could not adjust and longed for home.

But they had been lied to: the island had not been buried under lava. The Government wanted it vacated for its own naval needs.

Part of the fascination in the premiere production in Edinburgh was the withholding of the Dark Secret about the islanders, as well as their peculiar dialect and values. The cast was also excellent: they compelled attention and sympathy even with their great simplicity of expression and emotion.

Neil Pepe's cast at the Manhattan Theatre Club unfortunately wasn't nearly as affecting as the Edinburgh ensemble. I was underwhelmed and wondered why I had liked the play so much initially…

Richard Greenberg's The Dazzle [*]

|

|

|

EAST SIDE ELEGANCE--Reg Rogers & Francie Swift in "The Dazzle."

Photo: ©Joan Marcus/2002. |

|

Can this be a Bernard Shaw revival of Pygmalion—beginning, oddly enough, with Eliza's triumph at the ball? Or could this be an unjustly forgotten Somerset Maugham social comedy?

Or even a spirited script by Noël Coward or S. N. Behrman?

No such luck…

The evening—and not only for the trio on stage—is all downhill after this dazzling, promising visual moment.

Unfortunately, the moment Peter Frechette—as Homer Collyer—opens his mouth to utter impossibly tortured but almost meaningless rhetorical flourishes, it's clear that dementia and doom lie dead ahead.

Richard Greenberg—who has created such intriguing scripts as Three Days of Rain and Eastern Standard—has somehow rediscovered the Theatre of the Absurd. He was hot on its trail in with his recent Everett Beekin.

Aside from the opening moment, there is absolutely nothing that dazzles in this self-indulgent & depressing drama.

It is instead Greenberg's bizarrely imagined explanation for the Upper East Side deaths of the reclusive Collyer Brothers over half a century ago. Tabloids across America went crazy with this story.

When their dead bodies were finally discovered in their decaying old townhouse, they were found surrounded by ceiling-high stacks of unread newspapers. And piles of useless artifacts and clothing.

They never threw anything away. Finally, one of them was killed when some newspapers collapsed on him. His helpless blind brother, waiting to be fed, starved to death. [If only they had had mobile-phones then!]

In Greenberg's fevered imaginings, Homer is insanely, almost incestuously, jealous and overly protective of his effete and somewhat simple brother, Langley [Reg Rogers]. Lang, it's noted, may have had talent as a pianist, but he finally hated to let go of a single note…

Allen Moyer's initial set was an Historical Preservationist's Dream. Herter

Brothers walls, mantel, furniture, and costly decorative objects of all sorts.

A balcony with shelves crammed with finely-bound books.

As the isolation and dementia progressed, the Gramercy Theatre's stage became

increasingly crowded with towering stacks of newspapers and dangerous nets

of second-handers suspended overhead.

In fact, Moyer's setting was the most active and interesting performer of

the evening.

I have admired most of Greenberg's previous work—even some of his more bizarre

dramatic footnotes—but The Dazzle is such a disappointment.

Only a few minutes into the first act, I found it almost impossible to pay

attention to the convoluted language he had devised for Homer. Or the attenuated

semi-responses of Langley.

Francie Swift—as the ambitious and rebellious young Manhattan debutante

who is determined to marry Lang—was the only spark of life in the show. And

even she succumbed to homelessness, loneliness, starvation, and TB at the

close.

Not what you might call a dazzling finish?

David Warren directed. Too bad he wasn't working with a script on the Collyer

Brothers by Tony Kushner. Then, even the most artful or ornamental rhetoric

would have had some powerful content, along with its literary flourishes…

It's said that the seat next to the driver is the Death Seat. In Christopher

Shinn's disturbing drama, it becomes something else.

A voluble, well-educated African-American father has just picked up a confused

teen-age boy with whom he's made contact on the Internet. His object is [almost

pedophiliac] sexual gratification.

But he is almost fatherly in his concern for the boy's interests and feelings.

He is Out To Show Him a Good Time, as they used to say…

This is creepy stuff, including the failed encounter in a motel. What point

was Shinn trying to make? If any? That the boy is named, of all things, June

may be a clue?

Stay out of Internet Chat Rooms? Pick on someone your own age?

But these scenes were only half of the Four play.

The remainder was devoted to the male seducer's skittish daughter, staying

home to look after her invalid mother. One infers that the mother's condition

is inexplicably related to the father's nocturnal adventures.

The daughter has a very amusing would-be boyfriend-lover who wishes he were

Black. Not just part-black and Puerto Rican. These characters and their interactions

almost made up for the depressing encounter of the other half the cast. Pascale

Armand and Trevor Oswalt were very good as these sexually dueling teens.

Someone has to give new works a chance with professional productions. Even

when they don't click. At least half this play reveals real talent in the

playwright.

Without new plays, we'd be stuck with endless revivals of Oklahoma!

and The Crucible.

Christopher Shinn's Four [*]

Watching Four on the MTC's intimate rear stage, I was

reminded of Paula Vogel's How I Learned To Drive. In

that unsettling drama of an uncle tampering sexually with his niece as he helped

her steer and shift gears, one didn't even want to be in the back-seat. Let

alone be a Back-Seat Driver.

Monodramas/Self-Dramatization/Total Recall—

|

|

|

NOBEL PRIZE-WINNER--Alan Alda as Richard Feynman in "QED."Photo:

©Craig Schwartz/2002. |

|

Peter Parnell's "QED" [***]

The admirable playwright Arthur Giron—author of Edith Stein and Becoming Memory—has written an effective drama about the outspoken and unconventional mathematician/physicist Richard Feynman. The scientist-genius who "blew the whistle" on what was fatally wrong with the doomed space-rocket Challenger.It was given a small-scale production over on West 52nd at the Ensemble Studio Theatre. I admired it and hoped it might get an Off-Broadway production.

But perhaps Feynman is too prickly, too special a type, to sell tickets eight times a week in a commercial theatre?

Even the better-known and better-connected Peter Parnell's two-handed Feynman monologue—"QED"—has been playing the Vivian Beaumont two nights per week only. On Sundays and Mondays, when Contact has no evening showings.

Alan Alda has been enthralling audiences as Feynman on the verge of death from cancer. His intellectual curiosity seems heightened, rather than dimmed, by bad news that would destroy most men.

Although Parnell has included a bubble-brained girl-student to prompt some reactions from Alda/Feynman, this show is essentially a monologue, performed for a large audience which seems to have wandered into a college office with amphitheatre-seating.

It was imported to Lincoln Center by director Gordon Davidson, who originally mounted it at his Mark Taper Theatre in Los Angeles. Parnell's script was commissioned for the Taper.

Before Feynman and colleagues made the atomic bomb possible—you are with him and Oppenheimer at Los Alamos—in the original Latin, QED meant Quod Erat Demonstrandum. Thusly, the Proof demonstrates…

After Feynman's research on the mysterious motions of Nuclear Particles, it came to mean Quantum Electron Dynamics. Or some such term…

Alda was very engaging and played the bongo drums, supposedly used by him off-stage in a college production of South Pacific. Ironically, that's roughly the test-area where Feynman was able to observe the fateful detonation of the Really Big Bomb.

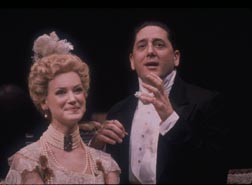

Lebby & Lollos' Mr. Goldwyn [***]

|

|

|

INCLUDE ME OUT!--Alan King IS "Mr. Goldwyn." Photo: ©Carol Rosegg/2002. |

|

As Sam Goldwyn tells the tale—in this enjoyable and ingenious mono/duodrama—he formed a film-making partnership with Edgar and Archie Selwyn, former owners of Broadway's Selwyn Theatre. [It's now the American Airlines Theatre on 42nd Street.]

They combined their names to create Metro-Goldwyn Productions. When Goldfish changed his name legally to Goldwyn, they were furious. They insisted the name belonged to them.

Mr. Goldwyn won his case, but he also pointed out to the Selwyns what a mistake it would have been to have used the other parts of each name.

They would have been Selfish Productions!

Usually—in bringing historic characters or charismatic celebrities back to life—the structure of the monologue works fairly well for adapters—with only one set, one performer, and often, only one costume.

But increasing Production Costs with a second performer—in this case Goldwyn's super-efficient secretary [Lauren Klein]—enables the Great Man or Woman to score points more effectively. It's similar to having a Straight Man feed cues to the Comic.

This also helps create the impression that an important day is actually in progress, in addition to the anecdotes shared with the audience.

Gene Saks has staged admirably, in David Gallo's imposing Hollywood Studio

office-setting. Mr. Goldwyn surely never read those handsomely bound books,

however.

Many of the most famous Goldwynism are recycled. King/Goldwyn insists most

of them were made up by his publicists.

Whatever… They are still funny, and they became his trademark.

Goldwyn's "Include me out" is on a par with those of his spiritual counterpart

in sports, Yogi Berra. In this show, It's déja-vu all over again!

Heather McDonald's An Almost Holy Picture [**]

|

|

|

AN ALMOST HOLY PICTURE--Kevin Bacon at prayer. Photo: ©Joan Marcus/2002. |

|

He is a disillusioned former cleric—now a cathedral grounds-keeper—who got the Call from God when only a boy. But this was a Light That Failed.

Bacon spends some of his time on stage putting pebbles into Mason glass-jars. These are symbolic. His beloved daughter has been born with hair all over her body.

A weird teen-age boy called Angel has photographed the girl in the nude. Hence, the title.

McDonald is even heavier on Symbols than she is on Poetry. At one point, the hero—called Samuel Gentle [yet another symbol!]—cribs from Matthew Arnold's great poem, Dover Beach.

It is somewhat appropriate in context. But it is not presented as a quote, garbled though it is. Can it be that the playwright is only recycling some phrases dimly remembered from schooldays?

Unfortunately, her own rhetoric is hardly on a level with that of Dr. Arnold, headmaster at Rugby. It is pretentious, even at times awkward.

This very pretension—this inflated poetic-prose—may well be what excited some leaden-eared critics.

But Mark Wendland's minimalist unit-set was spare without being entirely sterile. Kevin Adams created some impressively nuanced geometric lighting-effects which subtly set off some production moments that were not well served by the text.

Michael Meyer directed. He kept Bacon moving about, to create the illusion of action, although the evening is in effect Total Recall. It is a Memory Play, but without the redeeming benefit of a Meaningful Live Epiphany for Samuel Gentle on stage, mid-monologue.

This recalls the Enoch Arden Law: "Things seen are more powerful than things heard." Or, in the case of Gentle, "things remembered."

But then, who reads the novel Enoch Arden anymore? Who now reads Dover Beach?

Bea Arthur's Just Between Friends [***]

|

|

|

SHOUT IT OUT!--Bea Arthur on Broadway. Photo: ©Joan Marcus/2002. |

|

Stritch is now a far more self-aware performer—and she still has the voice for her signature-songs. She also has the advantage of a monologue artfully shaped by writer-critic John Lahr, son of the Cowardly Lion.

Arthur begins with hints of preparing leg of lamb. Hilarious to some.

But then she has only to mention a few names in show-business for her frantic fans burst into tumultuous applause. As though these celebrities had just come onto the stage…

Mere mention of her television series' roles in Maude and Golden Girls evoked equal ecstasies.

As I don't watch TV—teaching evenings or going to the theatre has long prevented onset of this optical illness—I had no fondly remembered images of what had provoked all the laughter and clapping.

Perhaps some old video-clips should have been included? Dame Edna certainly used them to good effect—and in the very same "tiny" Booth Theatre.

Bill Bailey's Bewilderness [**]

|

|

|

DEADFUNNY--BBC America's Bill Bailey. |

|

He seems an affable sort, with a special talent for musical parody. Indeed

the stage-decor is dominated by various electronic

keyboards and special-effects foot-pedals.

And he can also tell some amusing tales, largely about himself. This is

all offered in an artless, aimless manner, as though he is interrupting himself

without meaning to.

As Bailey is apparently famed in Britain for his laid-back comedy and music-making,

there must be something uniquely English about his comedy. He is seen on BBC

America's comedy series, Deadfunny.

Should he heed that old popular song: "Bill Bailey, Won't You Please Come

Home?"

Maybe. But if he had a clever director, an ingenious writer, and a good

designer, he could have a blockbuster of a show. He needs Focus and Structure.

Jason Robert Brown's The Last 5 Years [****]

|

|

|

THE LAST FIVE YEARS--Sherie & Norbert before career clashes. Photo:

©Joan Marcus/2002. |

|

If you think you have heard of a young composer named Brown before—and you are a Broadway Musical addict—this is the man. And the show everyone was talking about several seasons ago was Brown's Parade.

Staged by Hal Prince, it was an indictment of vicious and senseless anti-semitism in the Deep South. This led to the lynching—not of a Negro—but of a middle-aged Jewish factory-owner. He was unjustly accused to interfering with a factory-girl.

Although the critics were dismissive—and puzzled at Hal Prince's admiration of the composer's earnest work—they were most baffled by a Broadway musical with a lynching as its centerpiece.

Perhaps they had forgotten Prince's magisterial production of Sweeney Todd. Or of Grind?

Despite Parade's desultory run at the Vivian Beaumont, it went on an extensive tour of the nation. Well-received beyond the Hudson, it vindicated both Prince and Brown in the hinterlands.

Now, with witty Sondheim-style lyrics and attractive melodies, Brown's The Last Five Years seems set for a Broadway transfer and many regional productions. It stars the admirable Norbert Leo Butz and Sherie René Scott as the ambitious young lovers.

She is an aspiring actress. He's a novice novelist. She's a shiksa, and he's a Jewish boy. One who is proud to have married a glamorous goyish blonde—quite unlike all the Jewish girls he's dated.

The romance and the marriage gradually deteriorate as he rapidly achieves literary acclaim—and she continues to be rejected at auditions. Or get Nothing roles out there in Nowhere…

Brown's clever plot & musical conceit is to have his semi-autobiographical hero sing his songs—narrating his glowing new prospects—in a forward flow. As she is looking backward, seeing how and where things went wrong.

To some this may seem awkward, for the duo often seem to be singing past each other. Not in duets In The Moment. Not With. Not To.

Beowulf Boritt's stunning setting should be in the Whitney Biennale!

Effectively staged by Daisy Prince—Hal's talented director/performer daughter—The Last Five Years was premiered in Skokie [IL] at the Northlight Theatre.

Bryant & Frank's Aussie Prodigal [*]

The York Theatre's efforts to introduce new musicals—at a time when few make it to Broadway even via London—is admirable.But their available pool of new shows seems to be rather shallow. If not running dry altogether…

Prodigal, as the name suggests, deals with a favorite son who takes the car-keys and leaves home. Actually, he runs away from his father's fish-packing business in an Aussie seacoast town called Paradise for the excitements of Sydney.

So this lackluster show isn't even a new American musical, alas. And, like Edward Albee's goat-less Broadway drama, The Goat, there's no Fatted Calf on hand for home-coming festivities.

Because the restless young man's Problem is that he has grown up gay in a gay-bashing small-town environment, the wide-open sexual and social opportunities of the Big City almost undo him.

So he returns home, but his hearty male Dad still can't handle his son's sexuality. Nor can his jealous and untalented brother.

Even if this book were transposed to Point Lobos and San Francisco, these would still be uninteresting, unrewarding characters. Singing all-too-derivative songs…

Dean Bryant concocted the Aussie book & lyrics, with Mathew Frank devising the score. He played it himself on the Yamaha in the basement of St. Peter's Church on Lexington.

How about a Moratorium on Coming-of-Age Musicals featuring boys who have just discovered that they are Gay?

In our restless, eternal search for innovation in the Musical Theatre, perhaps we can now move on?

With the collaboration of Edward Albee, we could develop a ground-breaking new musical about a middle-aged man who falls in love with a goat named Sylvia…

Why not? It's a marginally more interesting idea than trying to turn Zola's Thérese Raquin into a Broadway musical. Almost as dumb as devising two versions of The Wild Party!

Revival Season on Broadway—

Vernel Bagneris' One Mo' Time Opens One More Time [****]

|

|

|

LIVELY LADIES SING THE BLUES--Female Stars of "One Mo' Time."

Photo: ©Carol Rosegg/2002. |

|

But the season's first big revival success is the jazzy, bluesy One Mo' Time, which first bowed in New York in the Village Gate's basement cabaret-theatre. It was lively and noisy and had a good long run.

In that incarnation, the show emphasized a plot-line that the performers onstage were actually playing on the infamous Southern TOBA Circuit.

The anagram signified "Tough on Black Asses," as racist white theatre-managers exploited their talented African-American artists.

TOBA references have disappeared—no longer Politically Correct?—but Wally Dunn does play a cantankerous, loud-mouthed white theatre-owner. He harangues audiences at the Longacre as much as he does Ma Reed's traveling song-and-dance troupe.

The time is 1926; the place New Orleans. But these tunes seem timeless. And audiences are still going crazy over them—as performed by the rubber-limbed Bagneris, and his co-stars: B. J. Crosby, Roz Ryan, and Rosalind Brown.

B. J.—a force of nature—is Ma Reed, with Bagneris as her handsome much younger company-manager, with an eye for younger female talents. Bagneris created this show, and he seems not to have aged at all.

The onstage band has been dubbed the New Orleans Blue Serenaders. They are pretty good, with some vocal solos of their own.

Artful Movements To Musical Monuments—

Mark Morris Dance Group at BAM [*****]

|

|

|

MARK MORRIS DANCERS AT BAM--World Premiere of "V." Photo: ©Robbie

Jack/2002. |

|

Interesting new restaurants are also opening in the area. Junior's award-winning cheesecake is no longer the only food-game in downtown Brooklyn.

But cultural—like social—changes are slow in coming. Nor do they always develop in the directions or ways planners have hoped.

A residential audience-potential—a surrounding community attuned to the arts—is also needed. BAM cannot continue to depend primarily on Manhattan culture-vultures. Nor on notable productions—heavily marketed—of outstanding foreign opera, theatre, and dance ensembles.

When Lichtenstein saved the noble Herts & Tallants-designed BAM theatre-complex from oblivion, he opened strong with four theatres soon programmed.

Today, what was the Helen Carey Theatre is the Rose Cinema. The Dodger Theatre space on an upper floor is no more. What was the Leperc Space above the main lobby is now the BAM Cafe, with dim lighting and indifferent cuisine.

True, the Majestic—now the Harvey—Theatre has been added to the performance venues. But it was initially conceived as Peter Brook's New York home, the mock-shabby equivalent of Brook's Paris Bouffes du Nord. This plan soon shattered, as Brook would not commit to annual visits with Parisian avant-garde experiments.

So the result has been very limited engagements of World Class performances. Even with two challenging programs, the Mark Morris ensemble was booked for only six performances. And it is just down Lafayette Street from BAM!

Nonetheless, sincere lovers of dance and theatre were grateful for those few opportunities to savor the excellence of Morris' remarkably diverse young ensemble. As well as to appreciate his ingenuity as a choreographer.

Mark Morris is certainly better known in Europe than he is at home. His choreographies and his dancers have been regulars at the Edinburgh Festival. His work is known from London to Brussels—where he has been chief of ballet at the Théâtre de la Monnaie—and onward to Munich, Salzburg, and Vienna.

One of Morris' distinctive qualities—which endears him to pure music-lovers—is his almost scholarly knowledge about classical and modern music. For Morris and his choreographies, the music is not mere accompaniment later selected to match to a movement concept that has taken place in his head spatially.

Ideas for new Morris choreographies often have their inception in particular pieces of music. For his recent Program A at BAM—with only one fairly new choreography—Morris chose an eclectic mix of music and movement.

I Love You Dearly was rousingly danced to three traditional Romanian folk-songs, sung in glittering costume from the orchestra-pit by Marisena Teicu Zamfir. She was accompanied on accordion, cembalon, violin, and keyboard.

It's a Mark Morris Hallmark to have live musical accompaniment—not tape—in the pit or on stage. This obviously increases production costs, but there are clearly apparent artistic advantages for both the dancers and the spectators. The choreography comes alive in every sense.

Program A also featured Monteverdi madrigals in a danced-answer to the initial offering. This was titled I Don't Want To Love. It was created in 1996, whereas the first piece was premiered way back in 1981. But both are as fresh, witty, and dynamically danced as though they were premieres.

The Artek ensemble replaced the Romanians in the pit. Obviously, it also costs more money to engage different groups for individual choreographies. Artistic Effect, not penny-pinching, is now Mark Morris' style. There was a time, however, when even taped music was valued.

Far distant from Monteverdi and madrigals was the music for the next choreography: Lou Harrison's Grand Duo for Violin & Piano, featuring Stampede, A Round, and Polka.

This energy-charged evening came to a triumphant close with Morris' Post 9/11 choreography, dedicated to the City of New York. This is V, danced to Robert Schumann's Quintet in E-flat, op. 44. It is an elegiac salute to the vibrancy and regenerative powers of Manhattan.

An amusing choreographic quirk that seems distinctive to Mark Morris is his abrupt way of clearing the stage of dancers who are not needed in new moments or movements. They simply scamper into the wings.

Morris himself danced in Program B's world premiere of Foursome—to music by the oddly matched Erik Satie and Johann Nepomuk Hummel. He's getting a bit thick in the middle, but he is still agile and amusing.

Cirque Éloise's Cirque Orchestra [***]

|

|

|

TURNING AROUND IN THE GERMAN WHEEL--Cirque Éloise acrobat in "Cirque

Orchestre." Photo: ©Alexandre LeGault/2002. |

|

Quebec's Cirque Éloise is not as artistically innovative as the better-known metaphorically Sun-soaked Soleil ensemble. But Éloise's young trapeze talents, jugglers, and tumblers are every bit as accomplished as their rivals.

They have appeared in Europe in smaller-scale, less ambitious and pretentious concept-shows than Soleil customarily mounts. Soleil's stunning Alegria, in fact, was recently in Singapore for Chinese New Year. On its extended Asian Tour…

In a major bid for New York recognition, Cirque Éloise did something rather unusual. It wedded its circus-specialties to audibly-miked symphony orchestra accompaniment. Hence the title: Cirque Orchestra.

This didn't really enhance the performers' artistry or skills. In fact, it may have inhibited them in some ways, attending to the semi-choreographic demands of the new production-concept.

Also, the loudness of the music sometimes threatened to aurally overwhelm the visual sensations of the audience.

But this program was offered as part of the Lincoln Center Great Performers Series. So it provided six performances of work for the Orchestra of St. Luke's, Manhattan's all-purpose pick-up band.

Nonetheless, Samuel Barber's beloved Adagio for Strings was wonderfully suited to Jano Chiasson and his Flying Tissue.

Contortionist Andréane LeClerc twisted herself into remarkable positions, to excerpts from Tchaikovsky's Nutcracker. Had she been a male performer, these contortions could have proved real nut-crackers…

Then there was Sibelius for the Aerial Rings. And Rimsky-Korsakov for the German Wheel.

Saint-Saëns' Danse macabre made the flying, fluttering, swirling Aeriel Tissue seem almost menacing. His Danse bacchanale, however, provided a riotous close to this odd evening's entertainment.[Loney]

Copyright © Glenn Loney 2002. No re-publication or broadcast use without proper credit of authorship. Suggested credit line: "Glenn Loney, New York Theatre Wire." Reproduction rights please contact: jslaff@nytheatre-wire.com.

| museums | recordings | coupons | publications | classified |